Work Hardening and When it Should Scare You

What Is Work Hardening

Work hardening is often an unintentional part of the machining process, where the cutting tool generates enough heat in one area to harden the workpiece. It results in plastic deformation which alters the physical structure of the metal being machined. This altered structure affects the machinability of the chosen metal and acts similarly to heat treating. When this occurs the generated speeds and feed requirements will be changed, creating a potential for inefficiency. This makes for a much more difficult machining process and can lead to scrapped parts, broken tools, and serious headaches.

Soften Up Work Hardening With Machining Advisor Pro’s Customizable Speeds and Feeds

What Causes Work Hardening

During machining, the friction between the tool and the workplace generates heat. The heat that is transferred to the workpiece causes the structure of the material to change and in turn harden the material. The degree to which it is hardened depends on the amount of heat being generated in the cutting action and the properties of the material, such as carbon content and other alloying elements. The most influential of these alloying elements include Manganese, Silicon, Nickel, Chromium, and Molybdenum.

While the hardness change will be the highest at the surface of the material, the thermal conductivity of the material will affect how far the hardness changes from the surface of the material.

Often times, the thermal properties of a material that makes it appealing for an application are also the main cause of its difficulty to machine. For example, the favorable thermal properties of titanium that allow it to function as a jet turbine are the same properties that cause difficulty in machining it.

Major Problems

Heat Generation

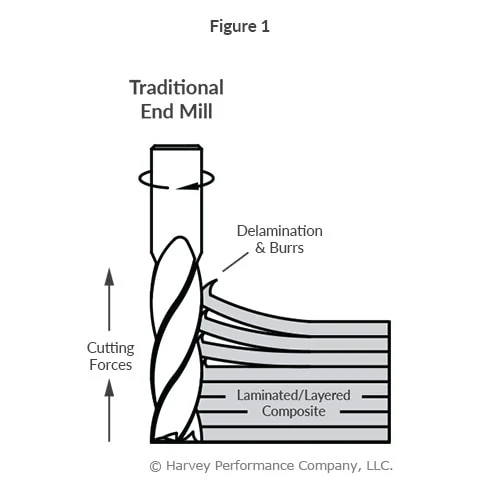

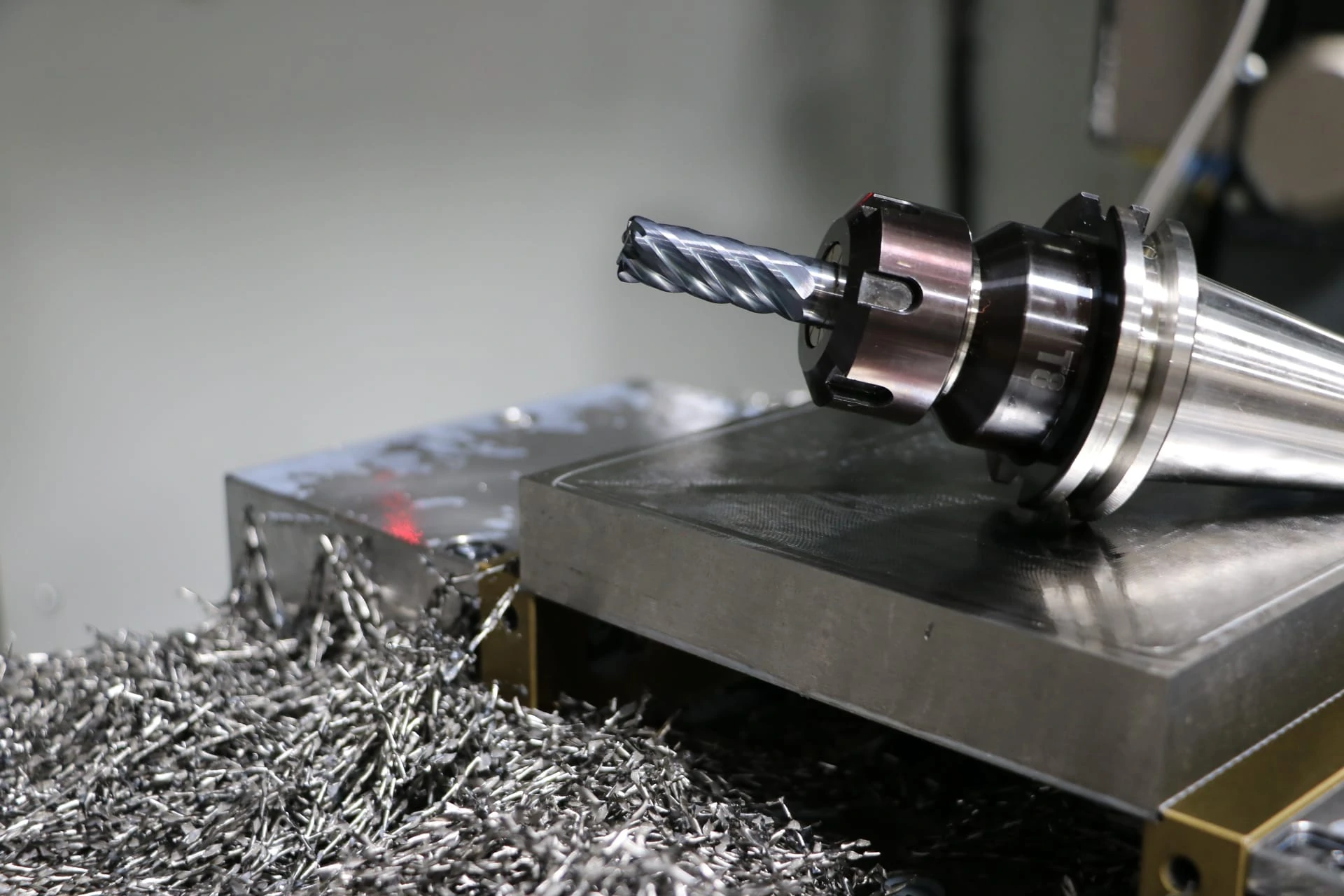

As previously stated, metal work hardening can create some serious problems when machining. The biggest issue is heat generated by the cutting tool and transferring to the workpiece, rather than to the chips. When the heat is transferred to the workpiece, it can cause deformation which will lead to scrapped parts. Stainless Steels and High-Temp Alloys are most prone to work hardening, so extra precaution is needed when machining in these materials.

Improper Speeds and Feeds

One other issue that scares a lot of machinists is the chance that a workpiece can harden to the point that it becomes equally as hard as the cutting tool. This is often the case when improper speeds and feeds are used. Incorrect speeds and feeds will cause more rubbing and less cutting, resulting in more heat generation passed to the workpiece. In these situations, machining can become next to impossible, and serious tool wear and eventual tool breakage are inevitable if the tool continues to be fed the same way.

How To Avoid Work Hardening

There are a few main keys to avoid work hardening: correct speeds and feeds, performing climb milling, selecting appropriate tool coatings, and proper coolant usage. As a general rule of thumb, talking to your tooling manufacturer and using their recommended speeds and feeds is essential for machining success.

Speeds and Feeds

Speeds and feeds become an even bigger priority when you want to avoid heat and tool rubbing, which can both cause serious work hardening. More cutting power and a constant feed rate keeps the tool moving and prevents heat from building up and transferring to the workpiece. The ultimate goal is to get the heat to transfer to the chips, and minimize the heat that is transferred into workpiece and avoiding any deformation of parts. Prior to machining, you should be setting guidelines for each cutting tool to ensure you receive the highest output without compromising on part finish or tool life.

Climb Milling

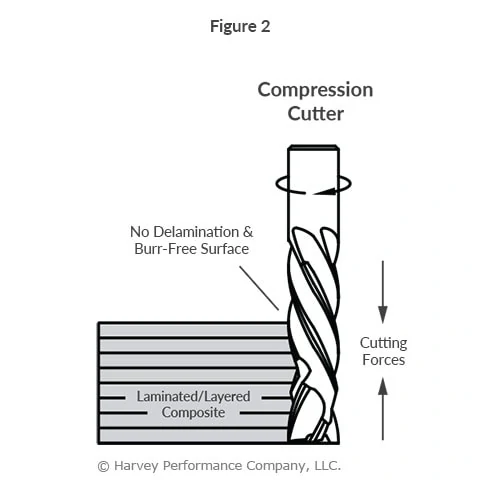

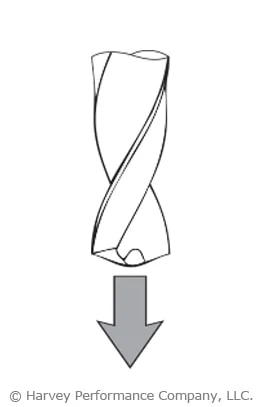

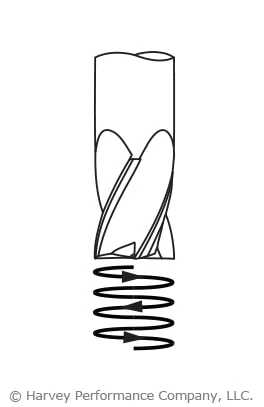

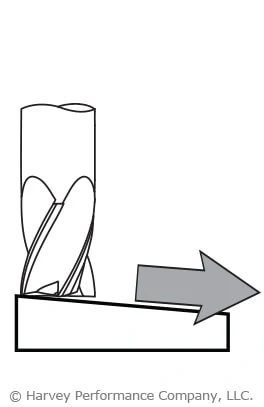

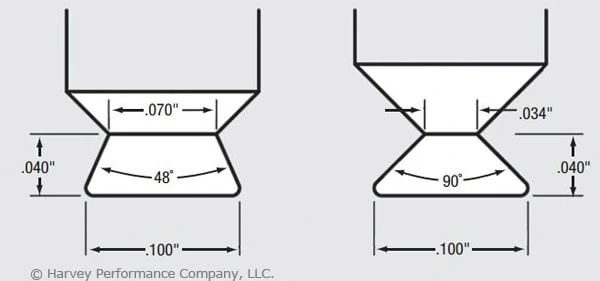

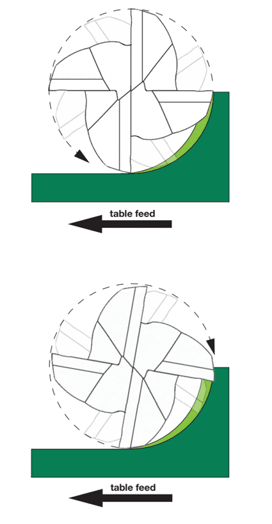

Conventional milling and climb milling are the two ways to perform CNC cutting operations. In climb milling, the cutter rotates with the feed, while in conventional milling the cutter rotates against the feed. However during conventional milling, the chip width starts at zero then increases thus generating heat at the workpiece. This results in work hardening and faster tool wear over time. On the other hand, climb milling begins at maximum chip width and decreases which transfers heat to the chip rather than the tool or workpiece. Climb milling is advantageous because there is less tool rubbing, minimized chance of chip recutting, and enhanced tool life.

Tool Coating

While friction is often the main culprit of heat generation, the appropriate coating for the material may help combat the severity. Many coatings for ferrous materials reduce the amount of friction generated during cutting action. This added lubricity will reduce the friction on the cutting tool and workpiece, therefore transferring the heat generated to the chip, rather than to the workpiece. Tool coatings also create a natural separation between carbide and the workpiece. This minimizes the internal temperature of the carbide as heat is transferred into the chips and workpiece.

Coolant

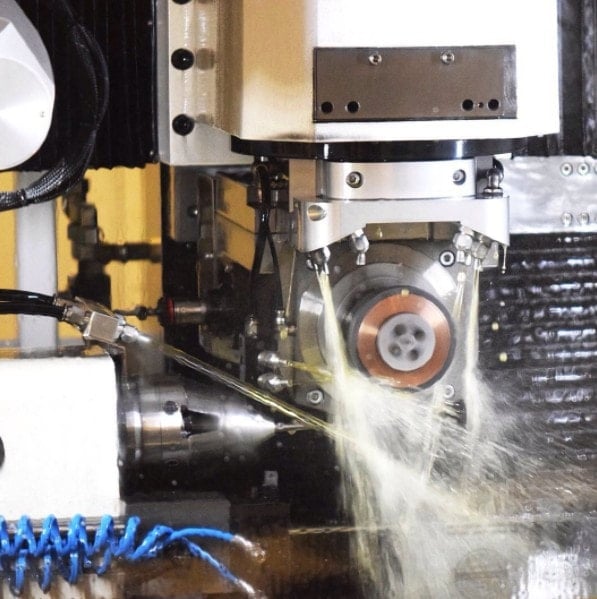

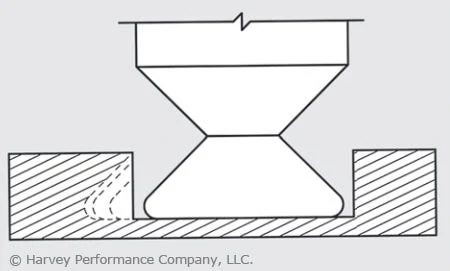

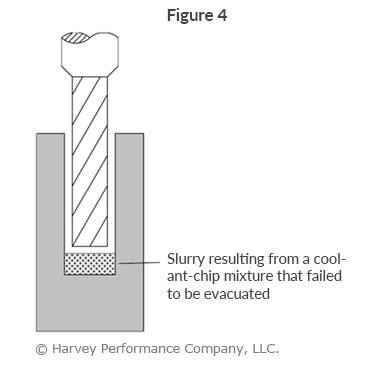

Proper coolant usage helps to control the temperature in a cutting operation. Machinists generally choose between using Flooding or High Pressure Coolant options. Flooding the workpiece with coolant may be necessary to maintain the proper temperature, especially when machining in stainless steels and high-temp alloys. This low pressure method creates lubricity to flush chips and avoid chip recutting which commonly damages cutting tools.

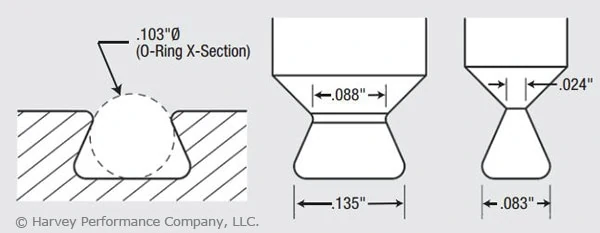

On the other hand, high pressure coolant delivers enhanced levels of chip evacuation and instant cooling of a part. However, one must be cautious of potentially breaking miniature diameter tooling when using this method due to the higher pressures. Coolant-fed tools can also help to reduce the heat at the contact point, lessening work hardening. While coolant-fed tools are typically a custom modification, saving parts from the scrap heap and using more machine time for the placement part will see the tool pay for itself over time.